The following article was written by Diana Bolander, Assistant Director/Curator at the Rahr-West Art Museum for the Art Forward Series.

Art, like everything else in life, is not produced in a vacuum. All artists are influenced by other artists, styles, and the world around them. Local artists participating in this year’s Members and County Exhibition at the Rahr-West Art Museum are notably wide-ranging in methods and inspiration. Looking around the 144 works in the gallery, visitors will see the influence of many artists. I experienced one of the joys of being a curator as I hung this exhibition in seeing the connections between local pieces and works from the Rahr-West’s collection. I checked in with the artists to find out more about how the convergences aligned with artists they identify as influences.

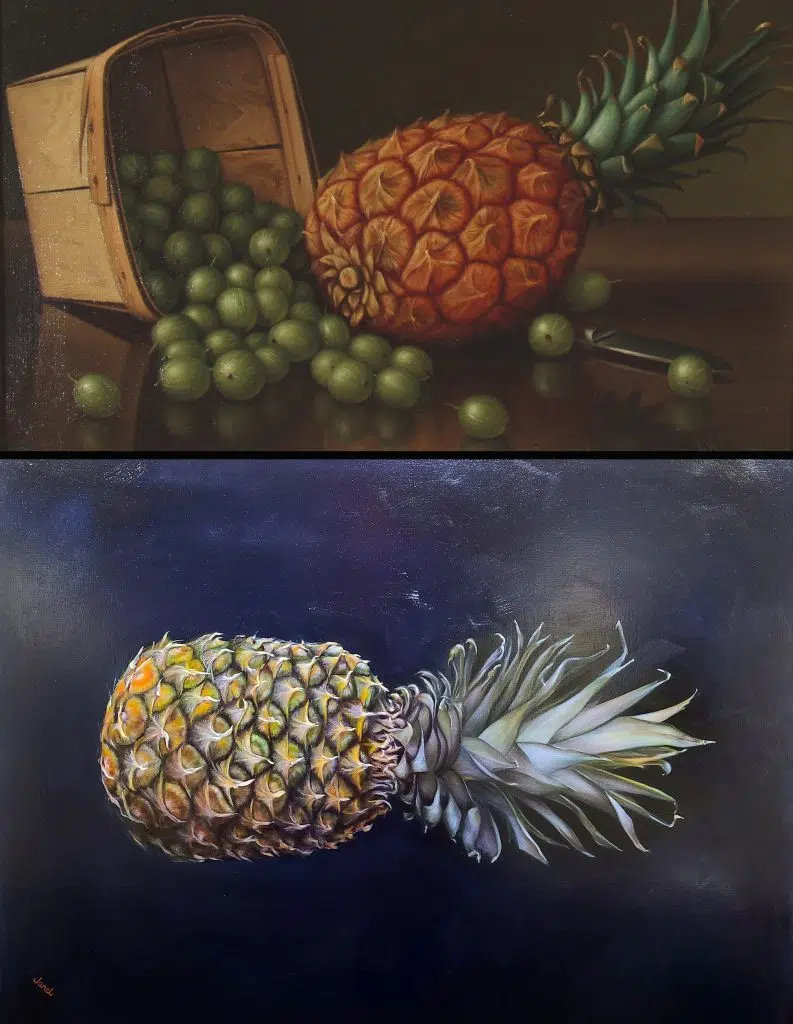

Levi Wells Prentice (1851-1935), Pineapple, Berry Box, and Gooseberries, Oil, n.d., 82.205.1

Janel Maples, Pineapple (Abstract Realism), Oil

Janel Maple’s Pineapple is reminiscent of a piece by Levi Wells Prentice that was probably painted around 1900. Levi Wells Prentice is best known for his still-lifes and landscapes of the Adirondack Mountains. The museum has several examples of his work including this pineapple, a raspberry bush, and a still-life prominently featuring a lobster.

Both paintings feature a realistic pineapple on a dark background, but that is where the similarities end. Maples’ pineapple exists in a dark void while Prentice’s is accompanied by a counter, fruit basket, and gooseberries. Perhaps the largest contrast between the two works is scale, Prentice’s painting is just under fifteen inches wide while Maples’ piece measures four feet in width. Notably, Maples’ first painting of this pineapple was life-size, but she repainted it large-scale to communicate “the imposing grandeur of this thing.”

Maples is heavily influenced by the realists, citing Bouguereau in particular. She says, “my art is about the challenge of authentic depiction, in [this case], exposing things about pineapples, like the orange and purple colors on the skin that a viewer might not have noticed. The addition of a background, setting, or other fruit would subtract from the object and ground it to an unnecessary, perhaps distracting, context.”

Her interest in the pineapple wasn’t about its being a symbol for welcoming in painting, but because it was available. Maples believes “paintings may be laden with deep symbolism and meaning, but sometimes a pineapple is just a pineapple.” Maples notes this particular pineapple was grilled and eaten in a salad after she captured its color and texture!

Wassily Kandinsky (1886-1944), Affiche, lithograph, 91.4.32, 1969, Gift of the Hooper Foundation

Judith LaGrow, Allegro, Acrylic

LaGrow’s abstract paintings reminded me instantly of the work of Kandinsky due to the bright colors and repetition of line and circles. Kandinsky is credited with creating some of the first completely abstract works in modern art around 1913. These works are aptly described as nonrepresentational; they reference no objects in the physical world. However, many of Kandinsky’s works did reference music.

Kandinsky, a cellist and violinist, was keen on atonal music. It inspired him to create art reflective of emotion. It is suspected Kandinsky had synesthesia, a condition affecting about one in two thousand people in which one sense like hearing, triggers another sense, like sight. He had an influential experience when attending a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin. Kandinsky stated, “ [I] saw all my colors in spirit, before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.” Kandinsky would often title his paintings with terms from music, such as composition or improvisation.

La Grow’s Allegro was inspired by music and Kandinsky. She plays violin in the Manitowoc Symphony and says she “borrowed the style of Wassily Kandinsky because he felt that music and art are intricately connected.” La Grow even made some of the shapes by tracing around her violin.

Untitled, Mark Tobey (1890-1976), 1967, Lithograph, Gift of Helen Powell Hooper and Mark L. Hooper

Debra Davis Crabbe, Every Sunny, Acrylic & Wax Pastels on Watercolor Paper

Debra Davis Crabbe’s work stands out due to the light color palette and expressive use of line. It actually brought to mind abstract artists in the collection like Karel Appel and Sam Francis, but due to the controlled color palette this work seemed to connect most strongly with Mark Tobey’s small print Untitled from 1967. Tobey was an Abstract Expressionist based in Seattle best known for his “white writing” style: an overlay of light-colored (usually white) calligraphic brush strokes painted over an abstract field of muted color. Tobey was influenced by Asian art, calligraphy, and Surrealist automatism, a method which the artist suppresses their conscious control allowing creation to be governed by the unconscious mind. Notably, Tobey, an internationally recognized artist mainly identified with Seattle and Switzerland, was born in Manitowoc County, in Centerville, in 1890 before moving to Chicago with his family in 1893.

Debra Davis Crabbe paints daily and works intuitively, using color, shape, composition, and marks to capture a moment in time and move the viewer in some way. She says, “I don’t usually start with a thought-out idea, but just start painting and the painting reveals itself to me. I make decisions about what to keep and what to add along the way.” She doesn’t try to emulate any specific artists, though she gets “lost in the fields of color of Rothko, the texture and the powerful colors of van Gogh, and loves the mark-making of Twombly.”

The above works by Debra Davis Crabbe, Judith La Grow, and Janel Maples will be on exhibit at the Rahr-West Art Museum through September 12, 2021 as part of the Members and County Invitational. Find more information on visiting and the works in our collection at www.rahrwestartmuseum.org.